Note: This will be the only newsletter for the month of May. I’m taking about a month off to do some research and thinking for the next few issues, which will likely focus on some deeper cuts in American food/cookbook history. Hope you get something out of this one, and I’ll see you in June!

Is it ever okay for a white chef to cook from another culture?

That question has been swirling around food media for the past few years and is getting more and more attention lately as people of color fight for more visibility and power in telling their own stories in the food world. We’ve touched on it a bit already, digging into the benefits of context and emotional resonance that come from writers of color sharing their cooking experiences. But I think that question is simplified to the point of being a copout—it’s engineered to trigger a defensive, white-fragile response. And anyway, the answer feels intuitively obvious—after all, it seems faintly ridiculous for everyone in the world to be limited to cooking only the dishes of their ethnic/racial background.

Still, I want to explore this question because unpacking it is crucial to advancing more equitable and respectful food media. And I thought The Gaijin Cookbook: Japanese Recipes from a Chef, Father, Eater, and Lifelong Outsider by Ivan Orkin and Chris Ying would be a good place to start.

Ivan Orkin’s claim to fame is his ramen shops. Currently, he runs two locations of Ivan Ramen in New York City, but he actually opened his first restaurant in Tokyo in 2006. He explains in the introduction to the book:

Gaijin (guy-jin) means “foreigner” or “outsider,” but it really implies something more like “intruder”...And even though I’ve lived in Japan for the better part of three decades, speak Japanese fluently, have opened two successful ramen shops in Tokyo, and am raising three half-Japanese kids, I’m still a gaijin.

Essentially, Orkin starts the book off both by trying to convince us of his Japanese cultural bonafides and recognizing his undeniable position outside of Japanese-ness. He and his co-writer, Chris Ying (a Chinese American writer and editor best known as a collaborator of David Chang’s and a co-founder of the magazine Lucky Peach) have a difficult needle to thread. They seem to know that they will wade into controversial waters if they position Orkin too aggressively as an “expert” in Japanese cuisine. Instead, they focus on his experiences of the food as an outsider but also as a father cooking for a family where he is the only white person.

I find myself pretty open to this approach. Maybe we’re finally at least moving beyond positioning single white authors as monumental, near-academic experts on one cuisine—as Paula Wolfert, Diana Kennedy, and Fuschia Dunlop built their careers on Mediterranean, Mexican, and Sichuan cooking, producing doorstop-sized cookbooks presented as the be-all end-all to learning about a country’s culinary culture. Instead, Gaijin Cookbook takes an angle more in line with what we saw in Xi’an Famous Foods: telling the story of your own, unique experience of a cuisine and what it has meant in your life.

As the introduction goes on to explain,

“...in general, I find that Japanese food often gets treated with over-the-top reverence in English-lanugage books, especially by my fellow gaijin, and I think that actually does the cuisine a disservice. Japanese food is not all precious, high-flying stuff. A Japanese life encompasses the same range of situations as an American one. There are busy weeknights and weekends when you feel ambitious, picky kids, special occasions, dreary winters, sweltering summers, picnics, potlucks, parties, and hangovers. And there’s food for every occasion.”

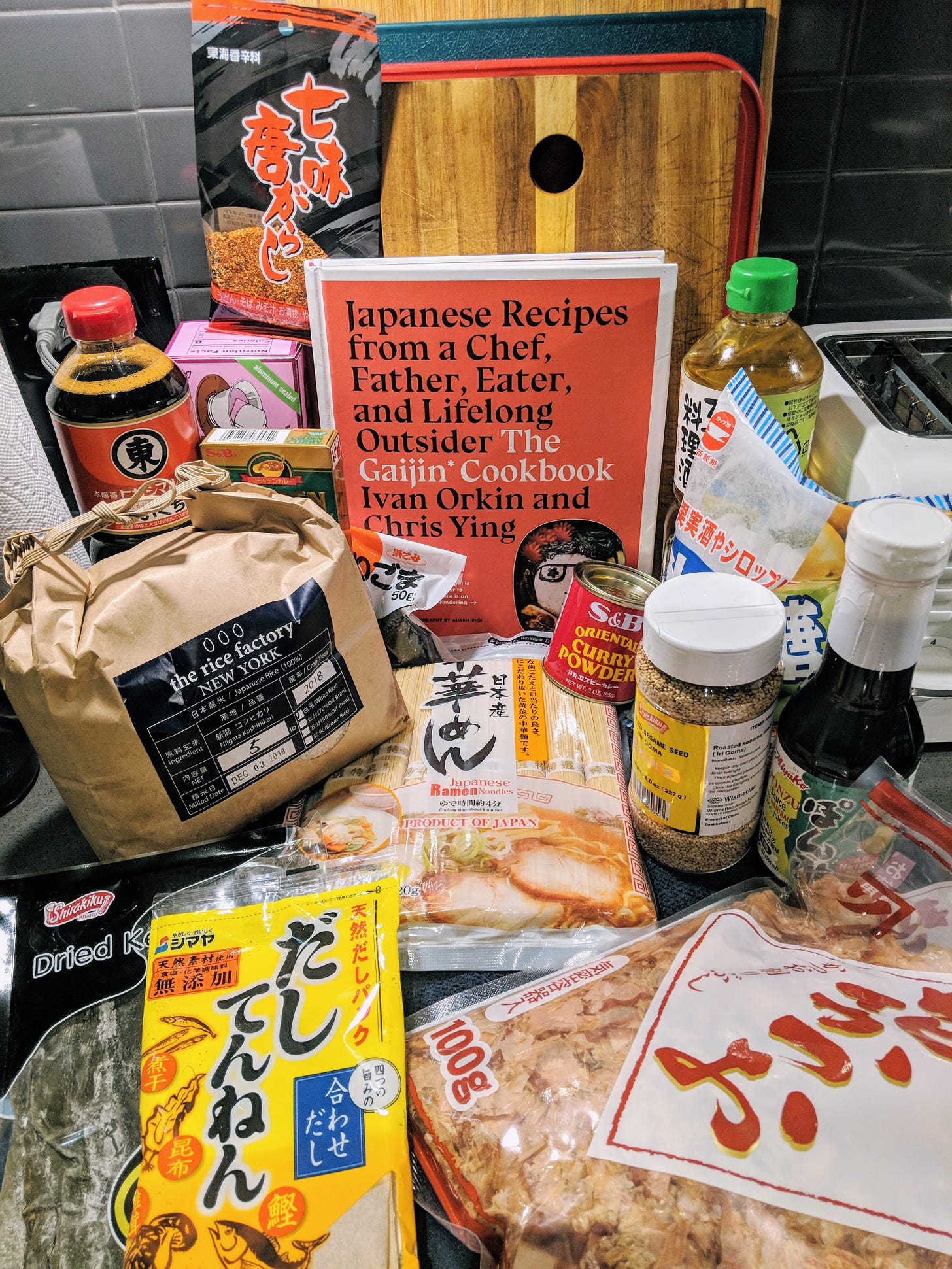

The result is a fun, evocative, educational, and highly cookable book. Ample space is given to the basics of Japanese cuisine; walking through essential building blocks like rice and dashi (an umami-filled broth usually made with seaweed and smoked fish); and providing a full glossary of ingredients, how to shop for them, and what substitutions work best if you can’t find them. Orkin also takes care to situate dishes in their cultural context, including a chapter dedicated to dishes that came to Japan from other cultures and another dedicated to foods made for New Year’s celebrations.

I came to the book having already made some popular Japanese dishes like okonomiyaki (savory pancakes usually made with shredded vegetables like cabbage), katsu (breaded pork or chicken cutlets), onigiri (rice balls I have been enamored by since seeing Ash Ketchum snack on them on the Pokemon TV show), and ochazuke (put leftover salmon on leftover rice, pour over dashi or green tea, and voila, a way to eat leftover salmon making your microwave smell like fish). Hence, my partner and I have turned to Gaijin Cookbook for some of its more involved recipes like tempura, sukiyaki (beef hot pot), and dan dan noodles (actually a Chinese preparation of noodles topped with spicy ground meat that’s popular in Japan). I even made Orkin’s recipe for mandarin vinegar, designed for Americans trying to capture the vibe of umeshu, Japanese plum wine, or umesu, plum vinegar, who may not be able to find the ume plums in the States. This required a huge jar of rock sugar, rice vinegar, and cut up oranges sitting in my fridge for a month, but it made great gifts for friends who finished it off faster than it took to ferment.

The recipe that I return to the most is the Pork Curry from the Box. Orkin explains what makes Japanese curry different from the Indian original (it’s usually sweeter and the gravy is often made with store-bought bricks) and presents the method that makes this dish most convenient for his family. They braise a whole pork shoulder in dashi at once, freeze it in portions, and then combine the pre-made pork with a few vegetables and a curry brick, which dissolves to make the gravy. (In this video for the recipe, he shows off his home technique for speeding things up even further by microwaving the vegetables to cook them faster.) The result is an incredibly rich curry that’s savory from the pork, slightly briny and smoky from the dashi, and has an enchantingly glossy sauce from the brick. On the next page, Orkin offers a recipe to make the curry from scratch using powder instead of a brick for those who want to cook “without the assistance of industrial food science,” although this version of the recipe also contains ketchup and Bull Dog tonkatsu sauce so I would take that claim with a grain of salt.

After getting to know Orkin’s curry recipe, I heard about a lauded recipe to make curry bricks from scratch, using 17 spices and a carefully composed roux of flour and butter. It turned out to be by Sonoko Sakai, a Japanese cooking teacher based in California. I continued to see her name pop up around the internet because of this recipe, and it turned out she had a cookbook about Japanese home cooking too...called Japanese Home Cooking. I thought reading it alongside The Gaijin Cookbook might provide a useful opportunity to see how a Japanese person approached the subject.

I haven’t positioned this letter as a dual review of both books because after spending about a month just trying to get through the first half of Sakai’s book, I accepted that I had made a mistake. Sakai is a proponent of slow food—preserving a culture’s culinary heritage by maintaining traditional scratch-cooking methods—and it means her approach to home cooking is completely different. The first section of Japanese Home Cooking is a very, very deep dive into the building blocks of the cuisine. Where Orkin spends a page explaining dashi and offering a basic and a vegetarian version, Sakai spends nine pages on it and gives recipes for five different versions as well as a profile of one of her friends whose family owns a grocery store that sells the components of dashi. She teaches you how to make miso, tofu, and three kinds of noodles from scratch. There is a short chapter dedicated solely to seaweeds. Essentially, her book is a reference text.

Even though it’s literally called Japanese Home Cooking, Sakai’s book is a different project and representative of a different lifestyle than the one Orkin and his family share. The Gaijin Cookbook is for a dabbler; Japanese Home Cooking is for the person who either wants to fully kit out their kitchen to produce very traditional Japanese cooking or just wants to learn about it in a serious way. I would argue that both approaches are “authentic,” in the same way that we now accept that making pasta from scratch and making Italian American dishes with dried pasta are both authentic, just different iterations of a cuisine.

But the difference between Orkin and Sakai is also an example of a dynamic I’ve discussed before of white writers taking on the role of being a “gateway” to a cuisine. Sure, Sakai has produced a reference text akin to those thick books by the likes of Fuschia Dunlop, but now that we live in a world where dabbling in a few different cuisines is more normalized for home cooks, a more superficial take is actually a faster path to popularity and clout.

Because most people just want the introduction and not the deep dive, white writers are better positioned to reap financial reward and attention. Their “blank slate” racial position is, for many, a more comfortable starting point for approaching a new cuisine, whether they are presenting a more personal take on the cuisine like Orkin does or the academic survey Dunlop is known for. That’s why, to me, it’s not all that productive to spend time dissecting how authentic a white person’s connection to a cuisine is.

The question isn’t who can or can’t cook this cuisine. The question is, who profits the most on the perception of their expertise?

We need to be thinking about systems more than individuals. That’s not to say there aren’t disrespectful and/or racist chefs and writers, because there certainly are. But racism is about power, and we need to criticize publishers and media brands that seek out and reward white experts and minimize opportunities for people of color to be the ones introducing outsiders to their cuisines.

That’s not to say there isn’t a workaround. Nowadays, we can turn to YouTube as easily as we can turn to a book to learn how to cook something. (Just One Cookbook is our go-to for Japanese food). Recipe developers of color are finding ways to build their careers through YouTube, Instagram, and as always, blogs. Still, they’re harder to find in a bookstore than they should be—and for the most part, they aren’t getting their own TV shows, either. They’re being locked out of the prestige of these platforms confer.

So I won’t tell you not to buy The Gaijin Cookbook because it’s by a white author, and I won’t tell you to buy Japanese Home Cooking because it’s by an Asian woman. But I will ask you to think carefully about the sources you turn to, how in depth you’re hoping to go, and how you can seek out creators of color to help you get there.

Marginal notes:

I feel like I should warn you that my partner and I found Sonoko Sakai’s curry brick recipe comically bland. Those who don’t have extremely well stocked spice cabinets will find it as challenging to source the 17 spices in the recipe as it would be to just order Japanese curry bricks online, so...just do the latter. Or if you are really uncomfortable about ~~chemical processing~~ giving you a curry glossy enough to appear in anime, buy Japanese curry powder instead, such as S&B brand.

One of the things I learned about from The Gaijin Cookbook was onsen eggs, a method of poaching eggs inside their shells which I will never stop being annoyed that I had never come across in Western food media before. Every time I watch this Just One Cookbook video demonstrating them I basically shout with delight.