What does a feminist restaurant look like?

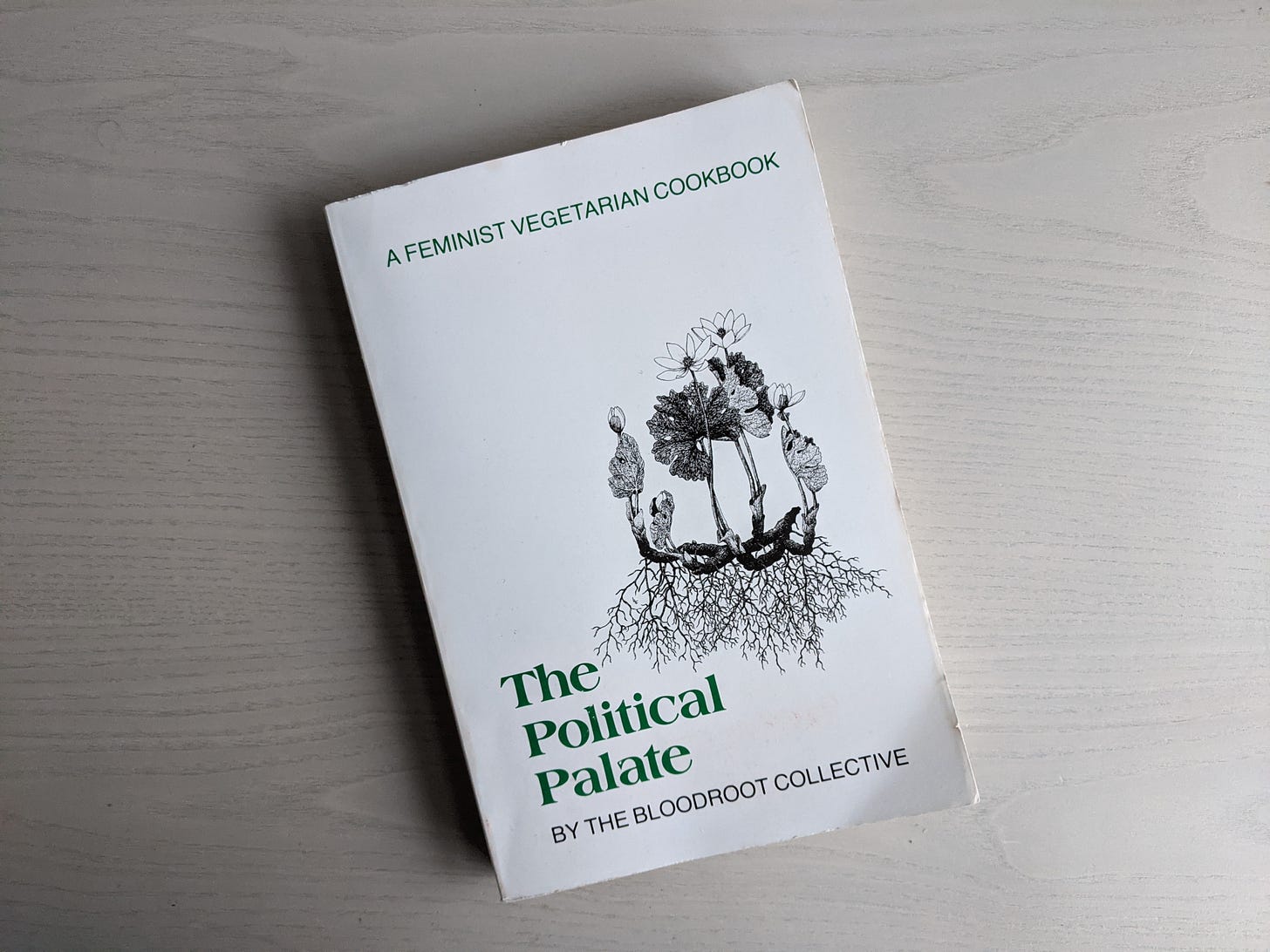

Reviewing The Political Palate: A Feminist Vegetarian Cookbook

Fun fact about me: I got my bachelor’s degree in Women’s and Gender Studies. Even though this was only a little over ten years ago, it was a very different time: even at a progressive university, I got into arguments with young women who made fun of me for caring about feminism and preferred to see themselves as “humanists.” It was just a few years before Beyoncé featured Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie’s definition of feminist on a hit record and before Janet Mock and Laverne Cox became household names.

In my first couple of years of study, several of the required classes for my major started with a discussion of the question, “what is feminism?” We tried to tease apart the difference between what feminism meant in the popular imagination—mostly, hating men and breaking glass ceilings—and what it meant materially. Our coursework was a catalogue of seemingly every way women were oppressed and marginalized. I read the original paper that coined the term “intersectionality” and traced the growth of unapologetically Black feminism from the ‘70s to the present day. Besides struggling to parse gender theorist Judith Butler, my education outside the bounds of the gender binary was more limited than I would like—enough that I recognized the gap even as I didn’t know all that I didn’t know.

I chose to major in feminism because I recognized that no liberal arts degree would map perfectly onto a career—so I might as well spend my time learning a way to think about the world. Centering my undergraduate education on the analysis of power has shaped my life, and I continue to try to deepen that knowledge now that I don’t have the benefits of a curricula or seminar discussion.

Now that you know all that about me, you can imagine how excited I was to get my hands on a cookbook where the introduction proclaims, “Feminism is not a part-time attitude for us; it is how we live all day, everyday.” This is The Political Palate: A Feminist Vegetarian Cookbook, the very first of many cookbooks published by the restaurant and bookstore Bloodroot in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Bloodroot was founded in 1977 by a collective of four women who initially met at National Organization of Women consciousness-raising groups earlier in the decade. With The Political Palate, the Bloodroot Collective set out their vision for the relationship between feminism and cooking. The remaining two owners, Noel Furie and Selma Miriam, have held fast to their founding ideology, demonstrating and disseminating it through the way they run the restaurant and the books on their shelves.

When I spoke to Selma Miriam in a phone interview, she shared that in every decision they made when founding the restaurant, they “tried to think about what would be the feminist thing to do,” from how the staff would be structured to which beers to carry. They wanted to “make sure everyone felt welcome, especially people who haven’t been welcomed in restaurants: women dining in restaurants, and people of color.” Feminism impacted their choice not to serve meat, too. The introduction of The Political Palate lays it out:

Our food is vegetarian because we are feminists. We are opposed to the exploitation, domination, and destruction which come from factory farming and the hunter with the gun. We oppose the keeping and killing of animals for the pleasure of the palate just as we oppose men controlling abortion or sterilization.

If you decided to skip the introduction or somehow ignored the title of the book, you still couldn’t avoid the Bloodroot Collective’s political position: tucked between the recipes are quotes from feminist writers and artists like Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, and Judy Chicago. And if that wasn’t enough, there’s an eight-page bibliography of further reading at the back of the book.

Because their feminism also dictates that their food be seasonal, to keep eating connected to “organic or natural timekeeping and the best efforts of the earth,” the book is divided into eight chapters based on the solstices, equinoxes, and divisions midway between, beginning with “witch’s new year on October 31.” As with most vegetarian cookbooks of the time, you can find just about every soup and salad imaginable, from Gingered Broccoli Stem Salad to Watercress Vichyssoise, but they’ll be separated from each other into chapters that reflect when their ingredients are at their peak. I was struck by the five different ideas for strawberries deserving of their short season in the Northeast, and an intense preparation of Spinach and Mushroom Crepes with Bearnaise Sauce that sounded like a great dinner party dish.

Like other books I read for this series the Bloodroot Collective rejected the “health food” tenets of vegetarian cooking, focusing instead on what was most exciting to them. I tried out a rice salad dressed with a bright red wine vinaigrette and studded with dried fruit, lightly biting red onion, and the crunch of bean sprouts and sliced almonds, and it became a treat to work my way through over the week. Later, I convinced my partner to get on board with an apricot walnut muffin recipe made with half whole wheat flour and sweetened with honey, swapping in some dried cherries pecans with the walnuts. They were tender and well-balanced despite the “good for you” ingredients that sometimes make one skeptical.

I was especially impressed by the book’s many dishes from other cultures. Of all the counterculture cookbooks I read this summer, The Political Palate was the least aligned with the “melting pot” approach to mixing and matching cuisines from around the world and the most interested in more iterations of dishes. There’s a Szechuan Noodles recipe that begins, “A trip to a Chinese market is necessary to make this dish” and calls for hot pickled turnip, Chinese sesame paste (tahini is notthe same thing) and fermented black beans. The Humus Bi Tahini, included as part of a Tabooli Platter along with a recipe for Baba Ghanouj, was refreshingly simple and normal after the sauteed carrot and onion version in the Horn of the Moon Cookbook. I was also drawn in by the Stir Fried Vegetables recipe, which is obviously another staple of any vegetarian cookbook of the time period. Bloodroot’s version included a huge bounty of summer vegetables with a simple sauce of tamari (gluten-free soy sauce), cooking wine, water, and cornstarch, as well as a healthy amount of minced ginger and garlic. I was pleasantly surprised by how delicious the simple sauce was and how successfully it brought everything together.

In the book’s introduction, Bloodroot’s founders emphasized their interest in vegetarian foodways from around the world. When I spoke to cofounder Selma Miriam, she affirmed that “to represent many different people and their foods” has always been their goal. She shared a story of visiting a bodega for the first time after opening the restaurant, which is located in a low-income, racially diverse neighborhood, and learning about ingredients she had never encountered before like yuca and calabasa. She recognized that it would be important to have a Puerto Rican dish on the menu, and learned to make a vegetarian version of sancocho, a stew with many variations throughout Latin America. More than forty years later, Miriam enthused to me about “what a miracle” it was to see the different methods of preparing rice and beans that her fellow cooks in the restaurant brought from their own immigrant backgrounds, and that part of the “riches of feminism is to know all these things people do and partake of it.”

That respect for the work of others is built into the restaurant from the ground up. Bloodroot has no chef: instead everyone cooks, and everyone contributes recipes and ideas. There are also no servers: you order at a counter, pick up your food when it’s ready, and clear your own table. With this unorthodox organizational philosophy, they’ve banished the requisite emotional labor of restaurant hospitality, abandoned the toxic masculinity endemic to the brigade system that normally decides how a cook advances in a restaurant (the traditional system is literally modeled on the military), and strived to create an egalitarian space where everyone’s contributions are equally valued. Miriam and Furie make a point to cite the sources of their recipes and share the spotlight, from the references and inspirations noted throughout The Political Palate to the space dedicated to Bloodroot’s Jamaican cook Carol Graham and her jerk seitan in a New York Times feature on the restaurant in 2017.

With their feminism driving how they’ve run Bloodroot for over forty years, I was curious about how their politics have shifted and how that might have impacted the restaurant. Bloodroot is now fully vegan, which Miriam expressed as the logical endpoint of opposing the exploitation of animals. But the simple answer to my question, “have your politics changed since you opened the restaurant?” was “no.” The women have found less and less that has inspired them in today’s feminist movement, and they remain grounded in the thinkers and ideals of what we now call the “second wave” of feminism that ebbed in the 1980s. They’ve ceased to include quotes from feminist texts in the cookbooks they publish every few years and there are few contemporary writers on the shelves of their bookstore because they find today’s feminism diluted from the fundamental goals of analyzing power difference and preventing the abuse of women. “The only thing I think of being positive,” Miriam conceded about today’s feminism, “is there’s finally good consciousness about racism.”

Recognizing early the importance of equity across not only gender but race and class, the women of Bloodroot were in many ways ahead of their time as feminists and as restaurant owners. But I was so disappointed to learn that they are disengaged from the vibrant and even more inclusive vision of the movement today. I certainly don’t disagree with the argument that “girl power” and #girlboss strains of pop culture have diluted the material goals of feminism, pulling the focus away from dismantling oppression. But we’ve also made advances in the past few decades, digging deeper into the power imbalances within our own movement and giving more space to women of color, trans women, and gender nonconforming people to help define what a better world looks like for all of us. To give up on contemporary feminist theory completely is to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

While researching Bloodroot I came across a troubling incident that took place a few years ago that caused people to levy claims of transphobia against Furie and Miriam, and it stands to reason that if their position on feminist theory is grounded in the past, their analysis of trans identity would be too. This is just one possible road we might find ourselves on if we’re too settled in our politics and unwilling to learn and change. A vision of welcoming the marginalized can only go so far if it isn’t tied to an up to date understanding of what marginalization looks like and means for different groups in the feminist community.

It was a real joy to leaf through The Political Palate and devour well-written, enticing, and thoughtfully-curated recipes interlaced with the feminist ideologies that formed the basis of the politics I dedicated myself to in college. Getting to know Bloodroot better and hearing Selma Miriam catalog all the ways she and Noel Furie had worked to bring feminist theory to life over 40 years of operation was truly an inspiration, showing what we can build when we put our politics at the core of all we do. I only wish I had the opportunity to see the way these thoughtful women would weave contemporary feminist theory into the world of food and what they could inspire in the next generation of feminists if they joined us in riding past the second wave.

The next issue will be the final one in the 70s counterculture series, and we’ll finally talk about the Moosewood Restaurant, the Ithaca spot which spawned the bestselling vegetarian cookbook in the U.S.