As the United States crawls into recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, the restaurant industry is at a crossroads. The layoffs and closures that swept through restaurants around the country last spring were followed by a series of revelations about worker harassment by big-name chefs. Food media conversations about the death of the restaurant turned to the death of the chef, or at least the end of the fawning attitude reporters had long afforded these figures at the expense of rank and file restaurant workers. It’s now been a year since those conversations kicked off, and the industry is facing a major labor shortage as food service workers re-evaluate if the poor pay and working conditions long taken for granted is worth the health risks of hospitality work while COVID continues to run its course.

For once, the balance of supply and demand is in favor of the worker, and restaurant owners are having to step up what they have to offer to potential employees if they want to rebuild their staffs. We’re also seeing the media gradually work harder to elevate the voices of restaurant employees and widen the scope of how a restaurant is evaluated and why it is given the spotlight. In this moment, we have the opportunity to reframe what we value from chefs and restaurants—and their relationship to the community should be a big part of it.

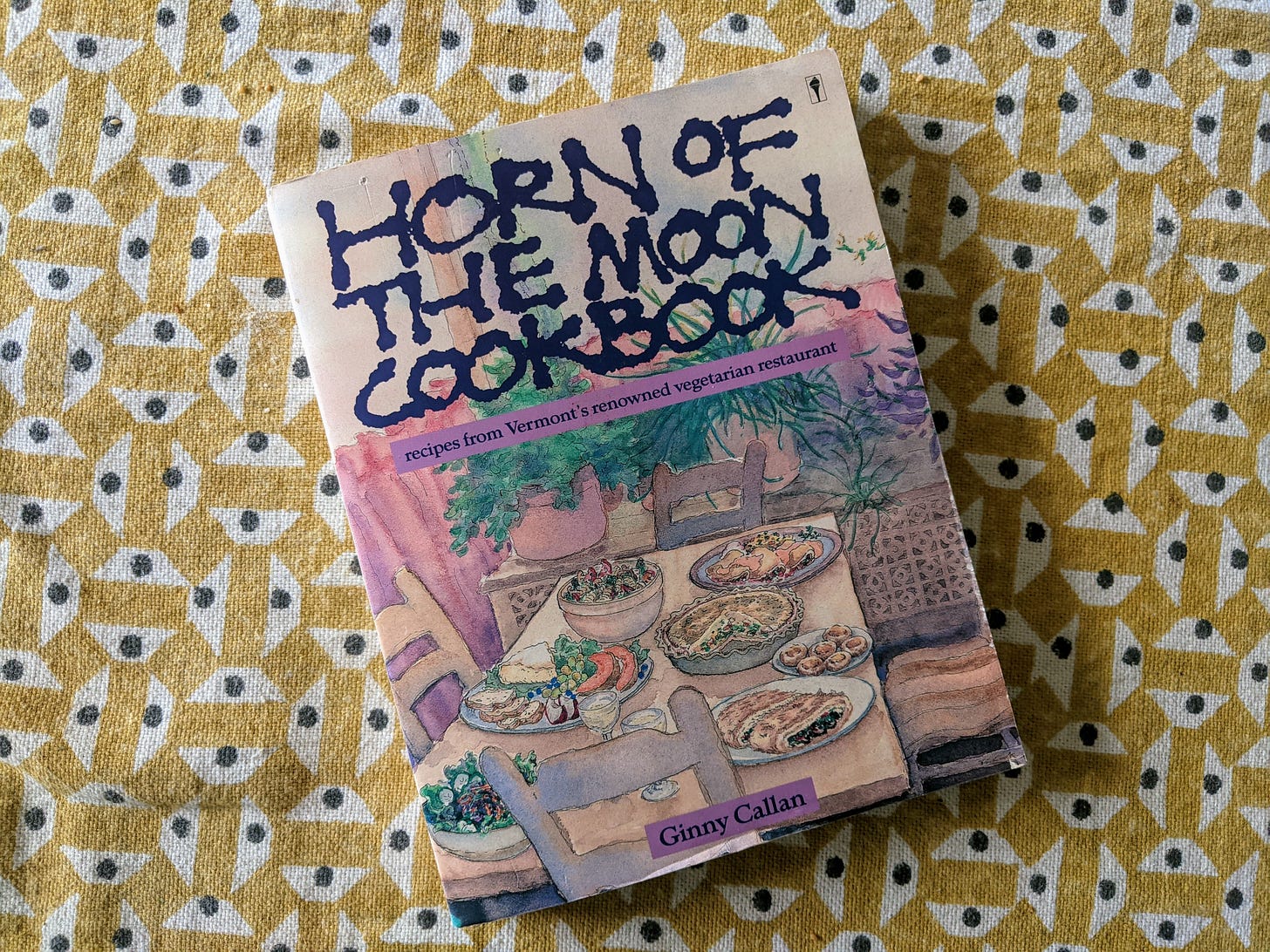

Crowded into the vegetarian shelf of a vintage cookbook store, this year I stumbled on a model for the community-minded restaurant: the Horn of the Moon Cookbook. Published in 1987, the book shares the recipes of the Horn of the Moon Café, vegetarian restaurant and countercultural gathering place opened in Montpelier, Vermont in 1977. From the first pages, author and founding chef Ginny Callan opens the door to the reader, letting them trade the chilly Vermont air for the warm aromas of freshly baked, whole grain pastries as regulars start the first pot of coffee when staff are running behind. The Horn of the Moon was a restaurant where politics lived not only on the menu but throughout the space, through relationships with both the local community and the staff.

In an oral history collected by the Vermont Historical Society, Callan shared that she “really wanted to serve good, healthy food that tasted good, was good for you, and was attractive—appealing to the eye.” Callan is vegetarian for humane reasons, and approached food according to many of the tenets of counterculture cuisine. She explains in the book’s introduction,

The café has struggled financially over the years. It has had to compete with other restaurants that use cheap and easy options. The fresh produce that we buy costs more than the canned or frozen foods many restaurants use, and it takes more time to prepare. We avoid using food additives. We also try to help support local farmers by buying their products. Our decision, made over time, has been to buy locally, organically raised produce in season, and to cook more with root crops that store well in the winter months. The sacrifice in profit is made up for by the good feeling we have about the food we serve.

Accordingly, the ingredients primer in the front of the book includes a section on “Basic Ingredients,” which explains that cooks should use whole grains for nutritional value, avoid ultrapasteurized milk dairy and the chemical additives that come with it, and shop for local, organic produce. The following section, on “The Less Common Ingredients,” introduces readers to vegan thickeners agar-agar, arrowroot, and kudzu; as well as miso, nutritional yeast, tamari (wheat-free soy sauce), tempeh, and tofu. The expansive variety of baked goods in the book—from cinnamon rolls and strawberry rhubarb pie to maple tofu cheesecake and carob chip cookies—rely on a mix of whole wheat and unbleached all-purpose flour, and eschew white sugar for honey and maple syrup. The café was the kind of place where a dish of rice, tofu, and vegetables, or “RTV,” was a popular seller for breakfast as well as lunch and dinner.

I went with the breakfast chapter for my recipe tests, inspired by a fascinating Poppyseed Almond Coffee Cake that was more of a massive bread filled with a sweet poppyseed and almond paste. I roped my partner into hosting a brunch centered on the book, and we tried out the asparagus omelet, home fries, and the restaurant’s “We Drink It” breakfast beverage. Though this book records the recipes of the counterculture, it was published in 1987, and has a noticeably more clear and specific recipe methodology than books of the ‘70s. The Poppyseed Almond Coffee Cake came together easily despite my standmixer being on its last legs, and though the mix of whole wheat and all purpose flour made the dough a little stiff, it was easy to work with and to craft into a braid-like shape using the beautiful pointillist illustration in the book as a guide. The omelet turned out rich, soft, and buttery, with the asparagus and cheese combining perfectly with the eggs. I made so many ingredient modifications to the homefries I can barely claim I tested the recipe, but its boil-then-fry method produced potatoes that were soft on the inside and crispy on the outside and I enjoyed the book’s addition of dill, which brightened up the flavors. We washed it all down with the café’s “We Drink It,” a mix of orange juice, grape juice, and sparkling water, but adapted it slightly to orange juice and sparkling grape juice, creating a sweet and fun mocktail mimosa.

The book offers the full scope of dishes served at the restaurant throughout the day, as well as an incredible chapter on adapting the recipes to cater a wedding of 100. You can find a recipe for just about any basic soup (many thickened with flour, butter, and cream); salads that go “beyond lettuce” with pasta, rice, couscous, and beans; and “simple meals” of dips and sandwiches. The main courses chapter depends on the theory of protein complementarity (popularized by Diet for a Small Planet and since debunked) which taught that those who avoided meat needed to eat several kinds of protein with different amino acid combinations at the same time in order for their bodies to synthesize the protein successfully. Hence, stacked dishes like the restaurant’s signature Luna Pie, with mushrooms, cheese, eggs, and tofu stuffed in a phyllo crust.

Just about every vegetarian cookbook writer of the period figured out that American and Western European meals were difficult to construct without meat, and Callan is no different, leaning heavily on Mediterranean, Mexican, Japanese, and Indian foodways for ideas. She proudly explains:

“The Horn of the Moon’s cooking has grown through the years and has drawn from many different cultures and cuisines to borrow from their best ingredients. These meals cross international borders, mixing oregano into burritos, tofu with pasta, and soy sauce almost everywhere. If only different governments could learn to mix so easily and well!”

This results in some unexpected combinations like those in the restaurant’s signature chapatis, Indian flatbreads stuffed with distinctly American combos like broccoli and cheddar as well as Japanese seaweed combined with spinach, alfalfa sprouts, and tahini dressing. And then there are the more bizarre recipes, like Miso Tofu Pizza with a sauce that includes tahini, basil, and parsley; and a hummus that for some reason has sauteed diced carrots and onions stirred in and is seasoned with tamari rather than salt.

Though this context-free, deracinating approach is considered more problematic today, at the time, being able to access these ingredients in a nominally American restaurant was groundbreaking. Callan’s openness to other cultures and their foodways was just another way she aligned herself with countercultural ways of thinking, even if her recipe interpretations could be misguided.

Most importantly, she found ways to incorporate her politics into the restaurant itself, outside the bounds of the menu. She recognized the importance of the labor that went into every part of the space: she made a point to hire local craftspeople to do the renovation when the restaurant moved to a new location; and avoided buying a dishwasher for years because “we felt, philopsophically, it was better to hire a person than to buy a machine.” All workers including Callan rotated jobs and pooled tips; and staff meetings took place monthly to make decisions through consensus. She would also occasionally close the restaurant so that staff could participate in protests, including anti-nuclear actions throughout New England that were a focus of Callan’s own activism.

Not only did the restaurant depend on the local farmers’ market for produce—staff sometimes ran across the street to said market for reinforcements if they ran out of lettuce—they exhibited a new local artist each month and hosted shows by local musicians. In her oral history interview, Callan notes that “It was a real scene for its time...a real hotbed for people who were involved in things to get together there.” Deep into the 80s, the countercultural vibe and progressive politics of the restaurant remained strong. A 1988 New York Times article describes the scene:

One counter holds pamphlets, petitions and leaflets left by patrons. Recently it held a flier calling for the boycott of Chilean wine and fruit; an exceptionally polite petition asking the United States Government to ''encourage the Chinese Government to stop their human-rights violations in Tibet,'' and campaign literature for Mayor Bernie Sanders of Burlington, Vt., a Socialist candidate for Congress.

For her part, Callan explains that,

While the Horn was considered a more alternative place, we’d get state legislators in there...and we’d get people coming in, just state workers, ‘cause they liked the food. So it ended up being a little bit of a cross-cultural meeting ground and fertilization space for those folks to start getting to know each other.

More than a hangout for counterculture types to signal their politics by eating vegetarian, local, seasonal, and organic, the Horn of the Moon Café was a “neighborhood spot” in the truest sense of the term. By elevating the health food rules of the time into dishes that were delicious and well-loved, Callan crafted an approachable menu that drew in all kinds of customers. She designed an institution that she believed was fair not only to animals and to the environment, but to her staff and local community members too, even with the recognition that these values ran counter to profits. In the end, her restaurant was so deeply rooted in the community that multiple retrospectives have been published about it by the local paper decades after the café closed in 1997.

In Horn of the Moon we can see a framework for how a chef can take responsibility for the wellbeing of their staff, community, and environment; working to create a better world that extends off of the plate.

Next issue: The Political Palate: A Feminist Vegetarian Cookbook and the story of the Bloodroot restaurant and feminist bookstore, still kicking in Bridgeport, CT over 40 years since it opened.

Stray observations: I couldn’t find a place for this in this piece, but another fun fact about Horn of the Moon is that they didn’t have air conditioning for environmental reasons, so one day a pair of regulars came in and attacked Callan with water guns in protest!