3,000 cookbooks is just the beginning

How cookbook libraries are expanding the historical picture of American cuisine

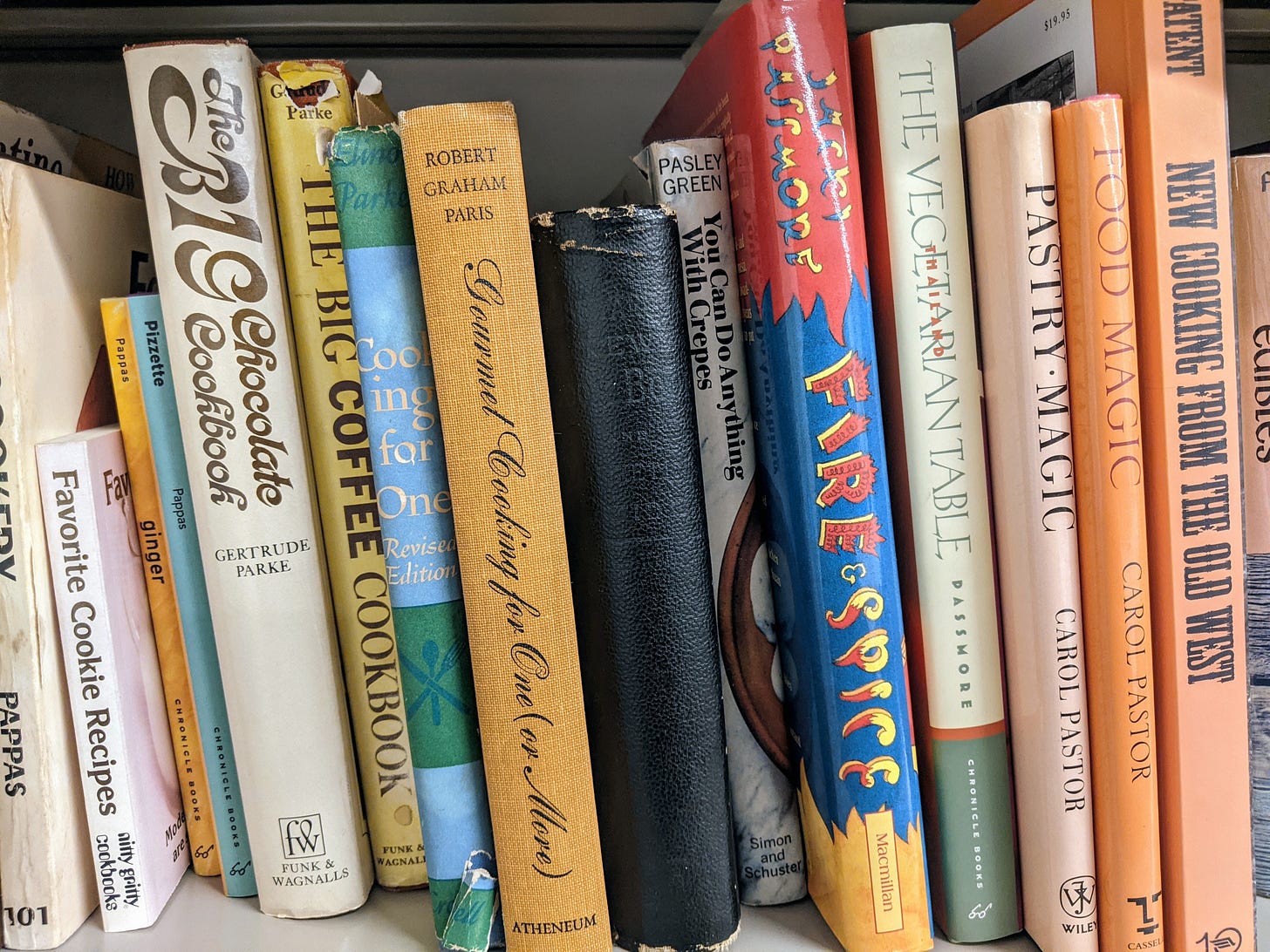

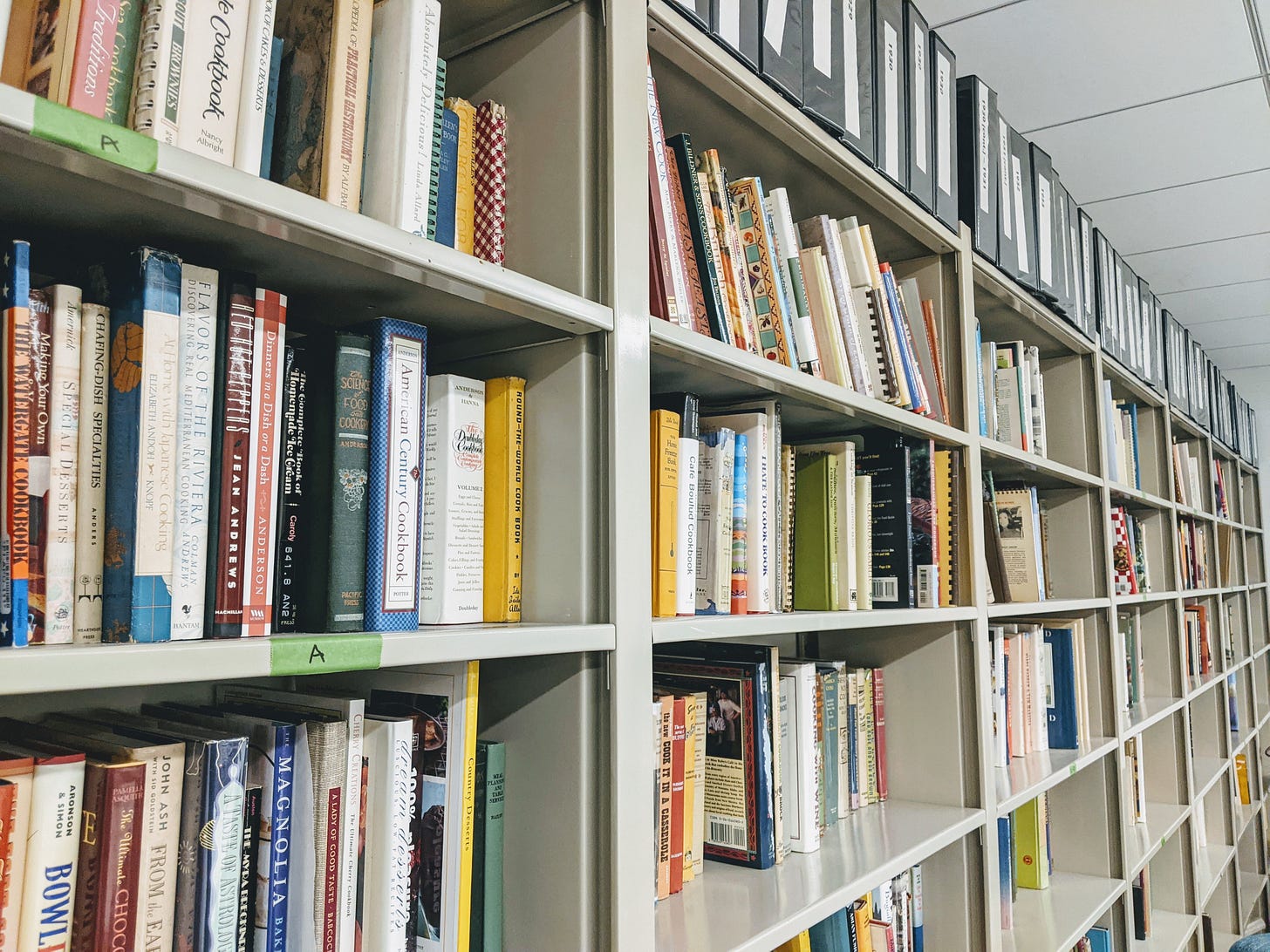

Tucked behind a door, off a side hallway, past the busy lounge at the Howard Thurman Student Center at Boston University, lies the home of the first academic food studies program in the United States. On any given visit to Boston University’s Gastronomy Department, you might see past the door of assistant director Barbara Rotger’s office, whose cabinets have tins of vintage recipe cards lined up on top; glimpse a professor setting up her laptop in a run of the mill lecture classroom; or spot students sorting through baskets of ingredients in an enormous industrial teaching kitchen. Take a few turns down the hallway and you’ll arrive at a seminar room lined on two sides with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. Those shelves hold 3,000 cookbooks.

To any home cook, the collection feels monumental—who can wrap their head around the existence of 3,000 cookbooks? But in reality, the B.U. Gastronomy library represents a narrow slice of culinary history, combining with Barbara Rotger’s recipe card collection and a menu collection donated by food writer John Mariani to offer visitors a survey of American cookery from the late 19th century to the present. Meanwhile, just across the Charles River in Cambridge sits arguably the best-known cookbook archive on the eastern seaboard (if not the United States) at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Schlesinger’s culinary collection holds over 35,000 books, along with thousands of recipe pamphlets and restaurant menus, largely donated from prominent women in American life as well as the food industry specifically.

Although the two collections were started 60 years apart and operate at totally different scales, today they’re both grappling with the same question: how do you curate your way to representing American cooking in all its diversity?

For both Boston University and Schlesinger Library’s culinary collections, years of very generous—and at times overenthusiastic—donations are the foundation on which everything else is built.

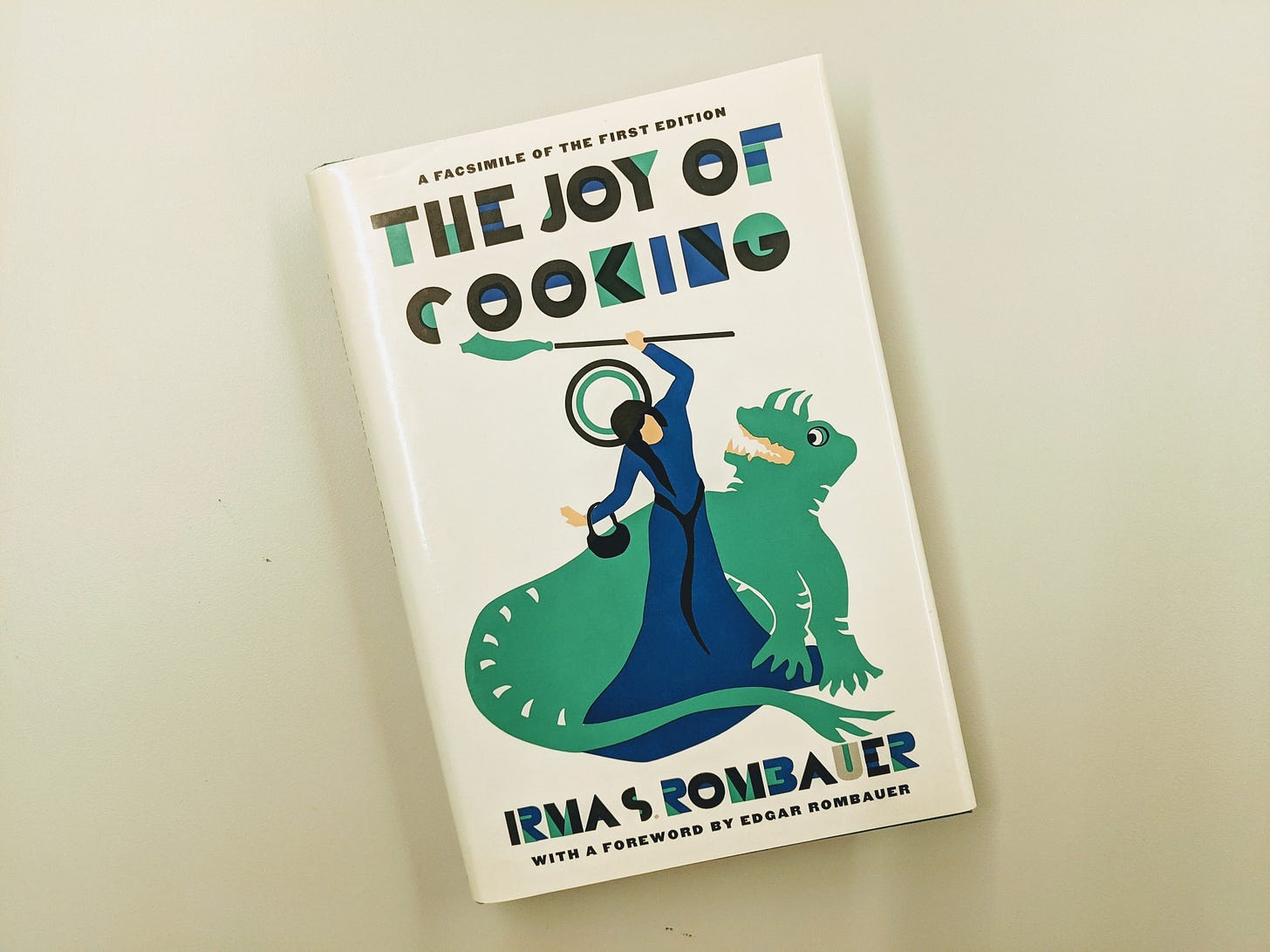

The culinary collection at Schlesinger Library was born out of the cookbooks that naturally started to accumulate at the Women’s Archive at Radcliffe College, founded in the 1940s. When you’re trying to document the lives of women in America dating back to the 18th century, domestic topics are pretty essential, and cookbooks are a part of that record. Marylene Altieri, Schlesinger Library’s Curator of Published and Printed Materials, shared in a Zoom interview that the library didn’t have an acquisition budget in its early years, and when it did, cookbooks weren’t prioritized, so that area of the collection was largely reliant on donations. In 1961, another of Harvard’s libraries contributed its own collection of 1,500 cookbooks to the Women’s Archive, and in that decade they started receiving donations of the personal papers of major food figures (and the library was renamed to its current title). The best-known of these is the archive of Julia Child, who started transferring her papers there in 1976—including not just the 5,000 books from her personal collection but gems like scripts for her T.V. show, her 1965 Emmy statuette, a copper pot and whisk, and her husband Paul’s cocktail recipe cards. This extremely high-profile donation led to even more. “So the library got used to thinking the collection could grow by donation,” said Altieri. “But then you’re not shaping the collection in a particular way—you get all kinds of random stuff.”

The collection at Boston University faces a similar problem. Started from a major donation of books around 20 years ago, it too has grown primarily from donations. After being invited to visit the library by assistant director Barbara Rotger, I spoke with the Gastronomy Program’s director, Megan Elias, in a Zoom interview to learn about the origins of their cookbook library and where it’s going today. “People would call and say, ‘I’m moving, I have 50 years of cookbooks, do you want them?’ or “My mom just passed, I have all her cookbooks, do you want them?’” she said of how they continued to acquire books after that first donation. “The policy was, just say ‘yes.’”

But with the finite amount of space in the room, the “yes” policy became problematic. When I visited last December I saw shelves and boxes full of donated books that still needed to sorted into the library proper. At this point, said Elias, “we started thinking about what we want in the collection and what it’s for.” They landed on a focus on trends in American cooking, geared toward use by students of the program.

“I want people to come into the library and if they spend enough time in it, to get the sense of what conversations were about food in the past 150 years in America—or at least published conversations,” Elias explained. She is an American historian, and her most recent book, Food on the Page: Cookbooks and American Culture, demonstrates the expertise she brings to this project despite not being a librarian by trade. "Because I have a pretty strong grasp of what the trends were in the past 200 years, I know what we should have if we want to be representative and I have an idea of what’s unique.” She aims to make strides toward both of these somewhat contradictory goals—such as both making sure the library shows the growth of Asian American cookbooks in the 1960s and beyond, and also holding onto an incredibly niche text like The Watergate Cookbook to give visitors viewpoints on major moments in American history through the lens of food.

Marylene Altieri has been doing her own curation calculus at Schlesinger Library. When she was hired in 2004, the library was shifting to become more selective about the donations it accepted. “There was a realization that we’ve become a catch-all–and was that really what we wanted the collection to be?” She started curating the donations with the driving question, “is there something in here that we need and don’t have, or is this just more of the same?” Meanwhile, it was becoming apparent that they would have to buy some books, because they weren’t getting donations of some texts they really wanted. Altieri was the first curator to be allocated a budget for culinary books, and while she found that she did want to collect “more of the same” to strengthen their strongest areas, she needed to look more critically at the kinds of books that they hadn’t received gifts of or purposefully collected.

For both libraries, the blindspots that came from building an archive from donations were striking. Altieri noted that Schlesinger had a surplus of European cookbooks because these books were sought after by their donors—especially those prominent food figures from the white upper class—but lacked a representative collection of African American and Asian American cookbooks. Elias told me about the day she realized the Gastronomy Program library didn’t have any books by Edna Lewis—now such a well-known Black food writer that she’s usually trotted out by some food publication every year for Black History Month—and purchased one immediately, because “we can’t have this library without Edna Lewis in it.” Without conscious curation and budgets for acquisition, both libraries were dependent on the taste of their donors. And the population who both know about universities with cookbook archives and have compiled collections worthy of donation is likely to be educated, wealthier, and…probably white. It follows that the cookbooks they had to offer wouldn’t exactly reflect the multicultural tapestry of American food culture.

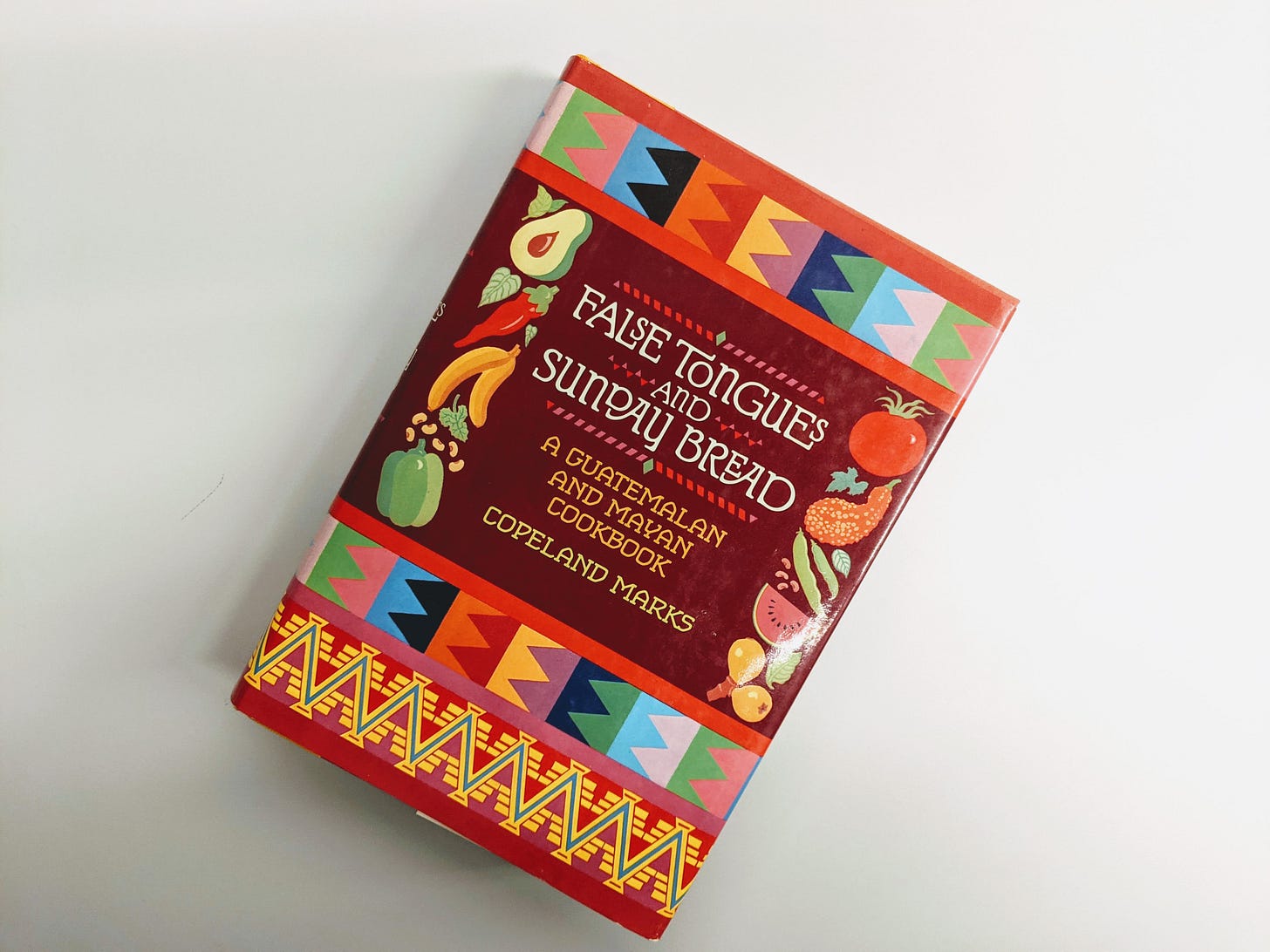

The problem goes deeper than the donors, though. When describing the picture she aims to paint with the Gastronomy Program’s library, Elias was quick to caveat the idea of “what conversations were about food in the past 150 years” with “at least, published conversations.” She noted that cookbooks by Latinx writers weren’t well represented in their collections, but there also really weren’t that many published in the United States as you would think. Altieri recognized the same issue for African American cookbooks, pointing out that “there’s not a huge printed history there”—and describing how many published and manuscript (handwritten) cookbooks by white women in the South are assumed to record recipes actually developed by Black kitchen workers. She also admitted that some major collectors of African American cookbooks have donated to other institutions.

On that note, Altieri is carefully considering how to provide a diverse scope of texts, while also being aware that the Schlesinger Library is no longer the only game in town. She keeps track of which other institutions have major collections in different subject areas and aims to ensure that if she doesn’t have something, she can source it from one of Harvard’s many partner libraries or point a researcher to another archive that is at least in the same region of the country. It’s this kind of wide-ranging awareness that has justified her project to collect the cookbooks of Josefina Velázquez de León, an incredibly prolific Mexican food writer and entrepreneur who compiled indigenous regional recipes across Mexico and published over 150 small cookbooks—through her own publishing company, no less. De León’s books are easier to find in California and the Southwestern U.S. than on the East Coast, so by seeking them out and making them more accessible in her region, Altieri is doing her part to strengthen scholarship on Mexican foodways.

Work like this is critical to make food scholarship possible outside of the predominantly white status quo of cookbook publishing. Both the Schlesinger Library and the Boston University Gastronomy Program are trying to provide a faithful representation of American home cooking while coming up against the fact that the usually white, upper class tastemakers who wrote, published, and bought the texts now archived in these libraries were not necessarily aiming for inclusivity.

But there are strategies to get around this. A particular focus of Altieri’s acquisition work is community cookbooks, recipe collections compiled by usually women-led groups and sold to raise funds for places of worship and other nonprofit causes. Communities of color and immigrant groups, excluded both from the conventional publishing world and access to credit and capital, managed to work collectively to raise money and get their recipes out into the world while they were at it.

Altieri has primarily been collecting community cookbooks from prior to the 1960s that illustrate this trend (after which “they become very generic”), but the self-publishing work continues today. Elias told a story of running a booth for the Gastronomy Program at the local farmer’s market where a young Dominican woman came by and shared that her grandmother had self-published a cookbook about Dominican food—a cuisine that the library has struggled to collect texts on. Elias is excited to bring the book in, and to keep listening to community members and students about what’s out there and what she’s missing that they want to learn more about.

There’s a common stereotype for communities of color, especially immigrant families, that our people don’t write recipes down, relying instead on oral transmission from mother to child and superhuman taste memory. It’s implied that the need for writing and recipe precision are a white people thing. But maybe what’s missing from that picture is the centuries that we’ve been locked out of the resources that would make it possible to record our recipes any other way. Maybe cultivating our food outside a written context is tradition with a dash of defense mechanism.

While the publishing world has finally deigned to elevate more voices of color over the past few decades, it will take real commitment from academic institutions to ensure that earlier, harder to find records of non-white foodways aren’t lost to posterity. Working with limited resources, Altieri and Elias are among scholars all over the country who are revisiting and redefining whose food is worthy of study, and giving researchers and journalists a wider landscape to explore and share with the world.

Marginal note: I unfortunately wasn’t able to visit Schlesinger Library in person, so all the photos here are from Boston University, but you can check out some of Schlesinger’s collections online, including Julia Child’s papers.